Directed by: Ridley Scott

The Martian, directed by sci-fi master Ridley Scott, and starring as good a cast of actors as you will find, may be the best movie this year. Taking place in what feels like equal parts on the surface of the planet Mars and in the various rooms of NASA’s Space Center in Houston, Martian is the story of Mark Watney, an astronaut who finds himself stranded on Mars with very little food, no communication with the outside world and only the shreds of hope he can muster from his indefatigable courage to at least try to survive. Scott (Blade Runner, Gladiator, Alien) is at his big budget finest, and the script is tight, fast-paced, funny where it might have been silly and moving where it might have been maudlin. The film is a triumph in every way.

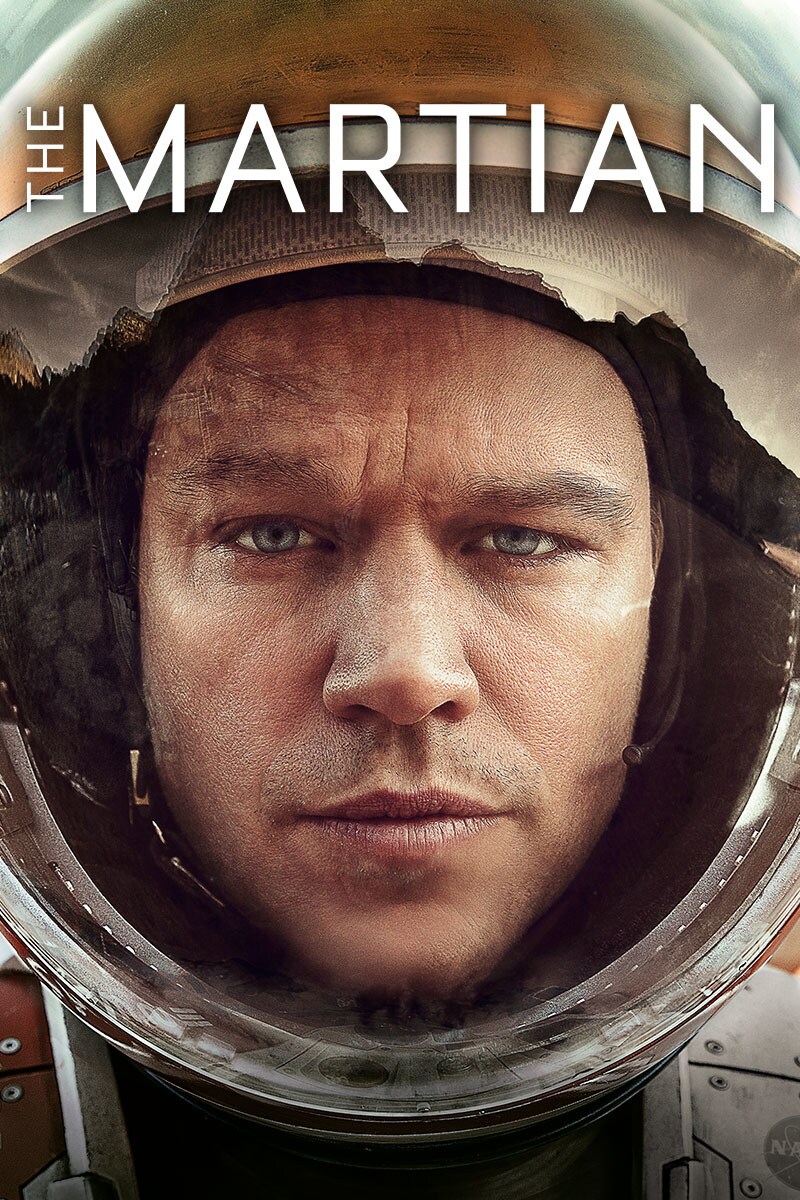

Matt Damon plays the indomitable Watney, and the role is a challenging one. The astronaut goes through highs of triumph and lows of defeat, and Damon plays them all with the same precision and intelligent ease. Surprisingly, the role has a lot of comedy, mostly sardonic, but humor nonetheless, and Damon, who showed how well he can play comedy in the Ocean’s movies, dwells seemingly effortlessly in that realm. Probably Jeff Daniels, as Teddy Sanders, head of NASA, and Chiwetel Ejiofor, playing Vincent Kapoor, the project manager, have the fullest roles outside of Damon, but Sean Bean, Kristen Wiig, and Mackenzie Davis add much to the dramatic decision making process on the ground, as the folks at NASA try to decide how and even whether they can get him home. In space, no less than Jessica Chastain, Michael Peña, and Kate Mara work towards saving their risen-from-the-dead colleague. Perhaps the only negative in the whole movie is how small the roles for Chastain, Wiig and Bean were, especially Chastain. To their credit, none of them mailed it in, and the movie is the better for it.

The great, unnamed character is the Martian landscape and the little compound Damon dwells in for much of the film. The sets are so believable, one forgets that in real life we have yet even to reach Mars, much less colonize it, and the glorious storms and silences are both equally believable and unique. The pace is masterful, too, as a movie that approaches two and a half hours in length felt too short, not because things were not explained or got left out, but because the viewer so enjoys himself, he doesn’t want the movie to end. Movies like this are usually much too long; not this one.

The only questionable aspect of The Martian is its underlying philosophy. Andy Weir wrote the novel (an incredible first novel) and Drew Goddard (World War Z, The Cabin in the Woods) adapted the screenplay, and their main theme is clear: when Nature goes up against the rugged human individual, especially one who is a scientist and an American, She is no match for him. Watney’s perseverance in the face of odds as insurmountable as odds can get is testimony to the human spirit first, but secondly to American ingenuity, especially that of the space program’s engineers. While there is a nod here and there both to the community of mankind and to transcendence, the burden of getting off Mars falls almost entirely on the astronaut’s shoulders and on the scientists back at NASA and in the spaceship, and they are up to the task. Yes, the Chinese help out with a rocket and, yes, Damon does speak once to a crucifix he discovers among his Latino colleague’s belongings, but these are small nods.

Perhaps in a world where few Christians spend more than five minutes a day in prayer or any other acknowledgement of God’s existence, we should not expect anything else. And of course there is no indication that any of the principals in the construction of the story are Christians; in fact, Ridley Scott has publicly proclaimed himself an atheist, though he apparently now self-identifies as agnostic. Why should we then expect them to produce a film that even bows to the self-doubt any Christian would have in this situation? Of course we shouldn’t.

Christians, of course, have the same capacity to act courageously as non-Christians, and I am not saying that what the story needed was a hand-wringing scene where Watney cries out desperately to God for help. What I am saying is that it would have been nice if, added to the humor and courage the character shows, a prayerful, humble attitude had surfaced, then Watney would have been a more palatable character for Christians to accept. It feels almost silly to want that in the face of such a likeable and admirable character as the astronaut is, but as a friend of mine once said in preaching on Matthew 5:16, “If you do good works and don’t acknowledge your Father’s role in the process, then all anyone is ever going to see is a good man.” Christians should always want God acknowledged in some way in their heroic actions. After all, does His presence permeate all of reality or not?

Drew Trotter

November 2, 2015