Directed by: Martin Scorsese

I love that the IMDb plot outline entry for this picture is a simple sentence: “A mob hitman recalls his possible involvement with the slaying of Jimmy Hoffa.” Like most simple sentences (that are true anyway), it hides a plethora of facts, thoughts, and meanings that could fill several books.

The Irishman may be master director Martin Scorsese’s finest work. Not only does it accomplish in feel and atmosphere what no one has ever accomplished like Scorsese, i.e. portraying the world of crime, especially the Italian Mafia, but it enters into almost all the realms of characterization, philosophy, and movie story magic that the master has ever visited.

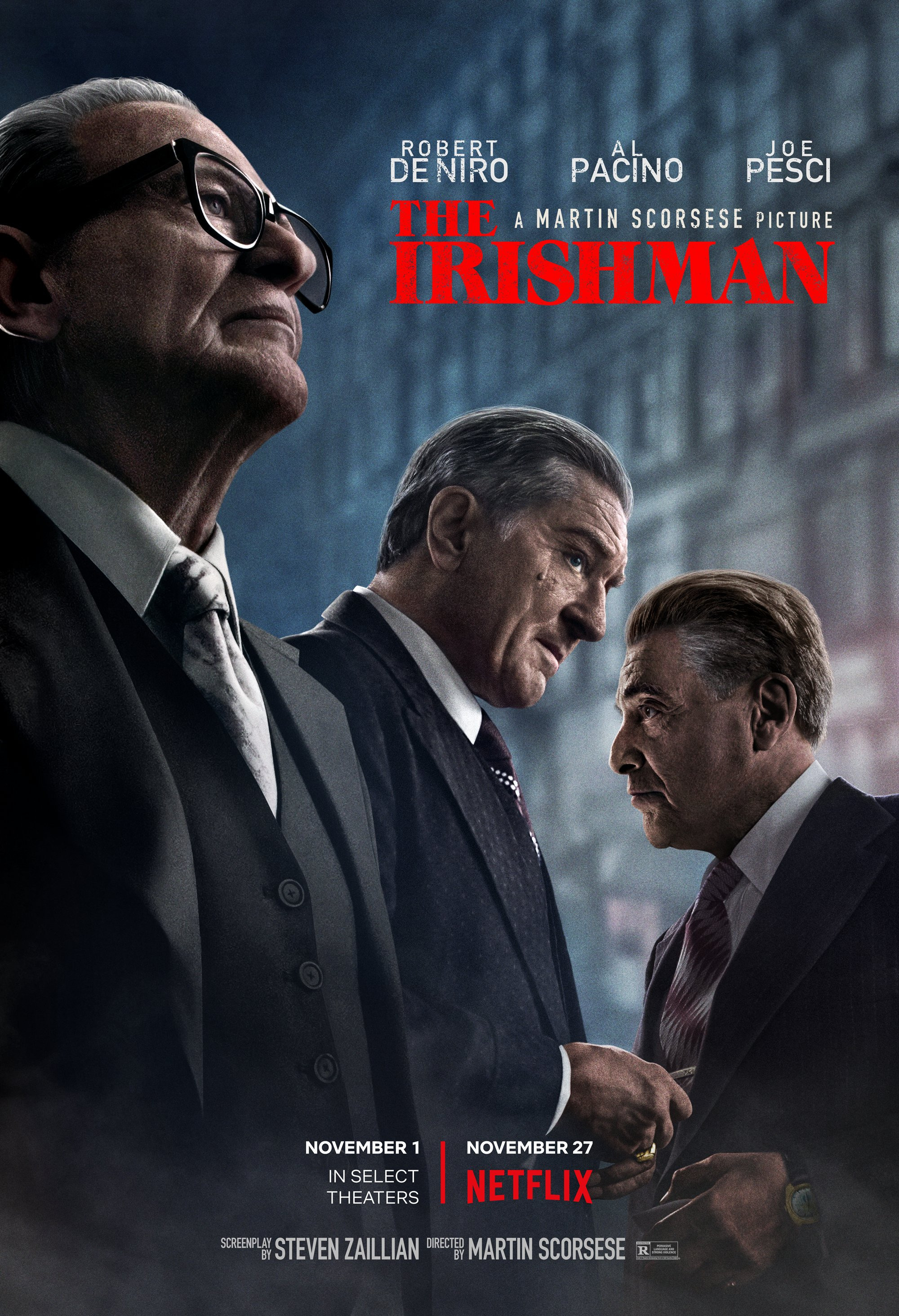

Starring Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, and Al Pacino, there is no reason even to comment on the acting. The supporting cast is superb with Stephen Graham, Ray Romano, Bobby Cannavale, and Jesse Plemons doing quite a bit of heavy lifting. Scorsese’s direction is flawless; I can’t remember when a three-hour movie was this captivating. And that viewer-friendly pace is accomplished with relatively little action. Amazingly, Scorsese has made a character-driven relationship film out of a mob-based crime story. And it is historically founded to boot, which adds another layer of difficulty (Did that really happen? Does it matter?) to the story.

This movie may go down in history even more for a technical innovation than for the better-known elements of filmmaking at which it excels. De Niro, Pesci, and Pacino are all now over 70, but they are playing their characters at everywhere along the timeline from their 40s to their 70s. To be able to make each man appear younger—smooth out facial wrinkles, slim down faces, necks, and waistlines, etc.—Scorsese’s crew invented a new camera able to accomplish this remarkable feat with very little intrusion into the actor’s space.

One humorous story illustrates how some things which demonstrate age cannot so easily change as wrinkles on the face. Pacino has a scene in which he, as Hoffa, is sitting in a comfortable chair in his living room with his family, watching a news report on John F. Kennedy. Hoffa intensely disliked Kennedy because of the way Robert Kennedy as Attorney General was cracking down on the Teamsters Union, and he gets so fed up with what he is seeing onscreen, that he leaps up out of his chair, swearing at the television as he leaves the room. When they were filming the scene, on the first take Pacino gets up out of the chair like a 75 year-old man would, and the camera man notices it, goes over to Scorsese, and points out to him how jarring this will be to the audience, given how young and virile Pacino will look on film. Scorsese agreed, but knowing how famously irritated Pacino can get on set, said to the camera man, “You tell him.” Pacino actually accepted the challenge and finally was able to leap out of his chair as a much younger man would do, and the scene was saved.

The film centers on a mob henchman named Frank Sheeran (De Niro), and is told in flashback through Sheeran’s eyes as he sits in a retirement home, thinking back over his life. Scorsese uses voice-over to fill in some information, but it is never used lazily. Sheeran was “loaned” as a bodyguard to Jimmy Hoffa when Hoffa became famous. The film chronicles Hoffa’s proud slide into oblivion, after his prison sentence causes his fall from grace as the head of the powerful Teamsters Union. Hoffa loses his grip on the reality that he is simply not as invincible as he thinks he is, and eventually he pays for his hubris with his life.

In history, of course, Hoffa simply disappeared; this film gives one (confessed, but not proven) theory of what happened to him. The movie shows the inch-by-inch way in which little decisions lead to ultimate ones, especially when attitudes and emotions like pride, anger, inattention, and unwavering loyalty get in the way of doing the right thing. There are several scenes at the end of the film demonstrating Sheeran’s remorse for his mob activity; confession, forgiveness, and absolution play an interesting role. One cannot help but be sympathetic toward the Sheeran, who through most of the movie talks about his mob work as matter-of-factly as a plumber would his work on the pipes of a house. At the end, though, the remorse seems genuine, as he realizes what he has done.

Sheeran’s remorse is worth dwelling on for a moment. The film opens with a long, hand-held tracking shot meandering down a hallway of what the viewer quickly recognizes is a nursing home. The people the camera passes are all with someone else. Significantly, the first couple passed, sitting in chairs facing one another and seemingly in animated conversation, are a young priest and an older woman. The camera continues its journey past groups playing cards, engaging in other games, eating with each other, until it finally comes to rest in front of, and facing, Sheeran as an older man sitting in a wheelchair. He is utterly alone in a remote room, unlike anyone else in the home. His alienation could not have been made more plain.

From this vantage point, Frank begins telling the story of his life from being a small-time trucker to joining the union to becoming one of the most trusted hit-men in the Italian mafia. His loyalty to the Buffalino mob was unwavering, but the viewer’s difficulty with Sheeran is he seems to treat his cold-blooded murders exactly like his earlier truck-driving: he’s just doing a job, carrying out orders, being a good company man. Late in the film, when he is reflecting on his life in the nursing home, we see flashbacks of him trying to make amends with family and God, but he is not sure at all how to do this or even what he has done wrong.

He tries to reconcile with his two daughters, who as adults have abandoned him. One daughter refuses to speak to him; she hasn’t for years. Poignantly, Sheeran can remember the date she walked out of his life so many years ago. His second daughter is willing to talk with him, but when she asks him what he is apologizing for, he simply stumbles around and can’t really answer. He is lost and confused about how to think about his life, a life he thinks he has led with honor and loyalty, but has made him a pariah in the eyes of society and his own family.

But when we see him at confession, though the scene starts with him having to be coached word-by-word what to pray, it ends with him praying, confessing his sins personally (though still not being willing to specify what he has done), and receiving absolution from the kind and wise priest, who tries to press him ever closer to true repentance. At one point, Sheeran says quietly, “What kind of man makes a phone call like that?” remembering, presumably, the call to Hoffa’s wife to console her, when he knows he himself has murdered Hoffa just a few days before, but Sheeran cannot bring himself to talk to the priest about the phone call specifically.

He stays in that state until the film closes with a remarkable shot of him in the distance in his bedroom, visible from the hallway only through a small crack in the door. Tiny, alone at Christmas-time, physically disabled, he has lost anything resembling life, though perhaps the crack in the door, left open by the priest at Sheeran’s request, speaks of the hope he has that redemption is possible somehow. The film ends on that shot with a cut to black. Is Sheeran truly remorseful in any meaningful sense of the word? The viewers must decide for themselves.

What can we learn from The Irishman? Perhaps the most important lesson is that of the need for us all to have a moral compass outside ourselves, governing how we act. The Irishman, like The Godfather before it, raises huge questions of family, friendship, and loyalty as values used to determine one’s actions. Good as these are in many cases, when any person makes one or more of them absolute, the person who does so is headed for trouble. With no ultimate moral code, much less any revelation, providing the means for making decisions, we all go astray like sheep without a shepherd.

Drew Trotter

April 7, 2020