Directed by: Quentin Tarantino

Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is Quentin Tarantino’s most recent movie and is set in Los Angeles at the time of the Manson murders. One of the most difficult tasks for a Christian when writing about film—far too large a discussion to do justice to in this space, but I need to mention it—is to balance the discussion of the quality of a film over against the view of the world that it espouses. When it comes to the genius of Quentin Tarantino, this assignment is especially problematic. Suffice it to say that in Hollywood, Tarantino’s superb abilities and his frighteningly corrupt moral sensibilities are both hugely on display.

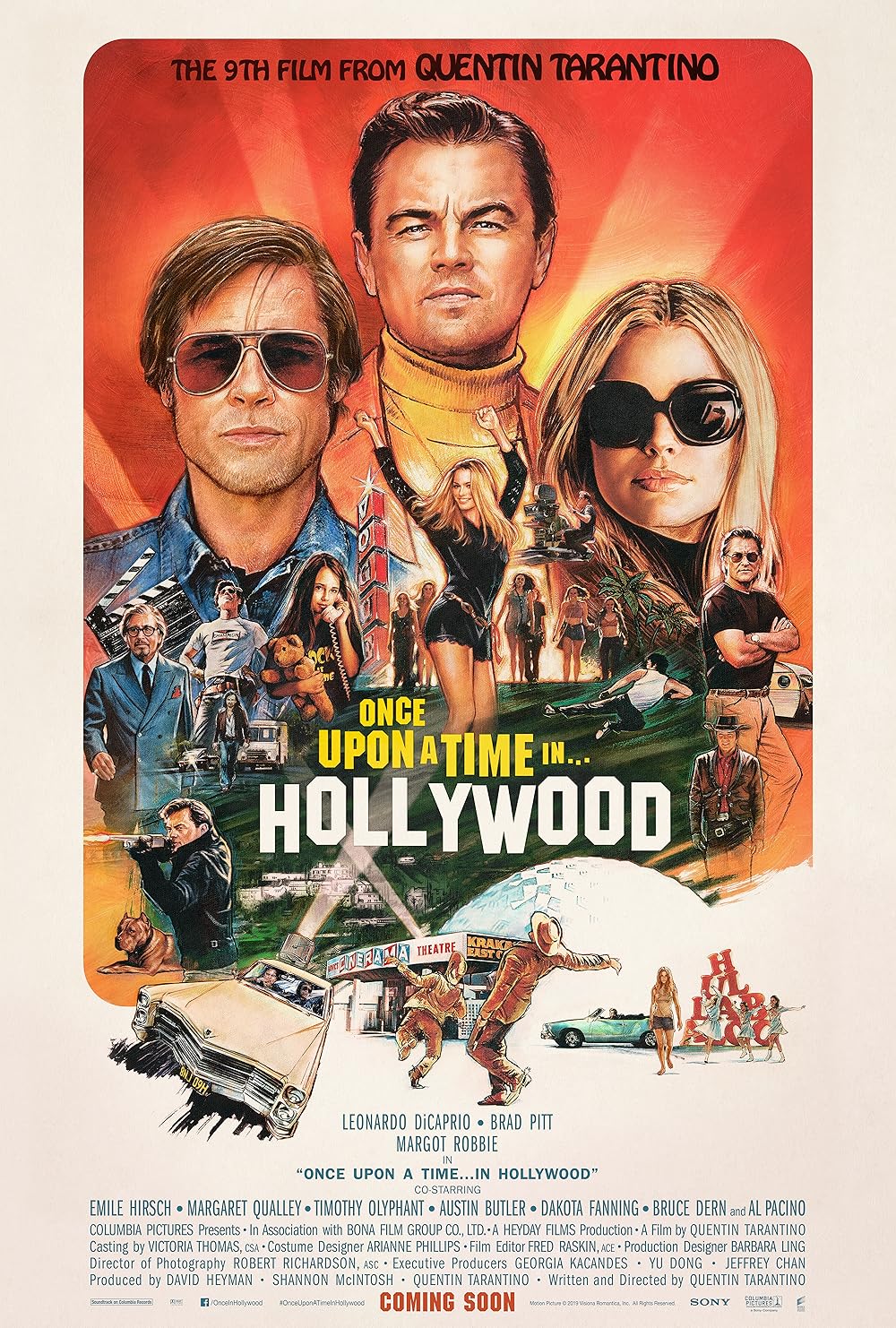

Hollywood is a masterpiece, the best film by Tarantino since the classic Pulp Fiction. The structure of the plot, centered in the idea constantly lurking in the back of the viewer’s mind that the Sharon Tate murders are waiting, serves perfectly a completely fictional story about Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), a self-doubting, wonderfully believable, television and movie star and his close friend and stunt man, Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt, who won his first acting Oscar for this role). DiCaprio is as good as ever, and it must be difficult to play a movie star, when one is one, because it is a certain type of confession: hey, you out there Mr. and Ms. Viewer: here I am with all my flaws, my pride, my vanity, my selfishness, my doubts, my second-guessings. There is an extraordinary scene, one of the best in the film, when DiCaprio does nothing but sit, stand, pace, smoke, drink, yell, and scream at himself, going over and over the mistakes he has just made in take after take of a scene, beating himself up, all in jump-cut, one camera seclusion. Perhaps only DiCaprio of all the actors in Hollywood today has both the star status and the self confidence to do this entirely improvised scene; I don’t know. What I do know is that the scene both fits perfectly into the film and stands out as a remarkable acting tour-de-force.

Pitt had perhaps as hard an assignment: he was supposed to play a stuntman, who didn’t care to be anything but the support for the star, and yet who has to carry a lot of the plot as it unfolds around the clueless, self-absorbed Dalton. He also does as good a job as he has ever done; I wonder how much he fed off the amazing DiCaprio and how much the reverse was true. In any case they were both very good under the sure hand of Tarantino’s direction. I felt sorry for poor Margot Robbie because her role simply didn’t allow the screen-time to do much. She also was very good, though, in what she did do, as was the remarkable Margaret Qually, Bruce Dern in a cameo appearance, and all the other supporting cast.

There were so many good things about this movie. The script was flawless, not only in its dialogue, but in its pacing, its twists and turns, and its all-important denouement. The locations were brilliantly used, the cinematography (Robert Richardson) as good as any I’ve seen in a long time, and the sets, costuming, and make-up perfectly matched to late sixties California. One could say the plot is too much like Tarantino’s World War II movie, Inglorious Basterds, but everything was so different between the two movies (except the presence of Pitt) that I don’t think many guessed the ending. When DiCaprio came out of his pool house with the flame-thrower, I thought what a perfect job the script did of tying up loose ends, and of making red herrings. DiCaprio had already been seen using a flame-thrower in a movie earlier in Rick Dalton’s career that mimicked the Inglorious Basterds scene of the killing of Hitler and his cronies in a theater, so the viewer was primed to think the quotation of that movie had already happened. Tarantino, who famously quotes shots, dialogue, and even plot points from classic Hollywood films, is now quoting himself, and justifiably so. Hollywood is just a superb piece of filmmaking in every way.

As great as this film is as a work of art, Tarantino’s moral foibles are, however, on show once again. His nihilistic world-view, so deeply embedded in the ultra-violence that is a chief element of all his movies, comes out again, in the violent killing of the three attackers, who enter Dalton’s house, bent on killing anyone there. Heads are repeatedly bashed against walls, people are cut up with knives and burned alive; the violence is gory and extended, as only Tarantino can do. It is only fair to mention that in this film, though, bloodshed and mayhem are limited to this last scene, and that the victims here certainly get what they deserve (cf. e.g. the poor guy in the back seat of the car in Pulp Fiction!). For the viewer to be able to say at the end of the film, “This is the way it should have happened,” as I did, is at least something, though the Christian knows that vengeance is not ours, as we sometimes think it is, and as Tarantino regularly espouses.

Quentin Tarantino has always delighted in putting the hilarious alongside the super-disturbing, wrenching the viewer back and forth between the comfortable and comic on one side and the disconcerting and brutal on the other. He once said of Pulp Fiction that he was seeking to make a movie where at any moment, the viewer might be either falling off their chair laughing, diving under their chair from fright, or doing both at the same time. To entertain customers in this chaotic, anarchic way, building in them an experience that travels with them outside the theater, encouraging them to embrace a disordered view of life, is ultimately destructive and, yes, despicable. Add to that the positive portrayal of bloody vengeance as a noble virtue, and this is even more so. But you have to appreciate his ability to pull off exactly what he is attempting. Excellence has its evil face, too.

Drew Trotter

May 19, 2020