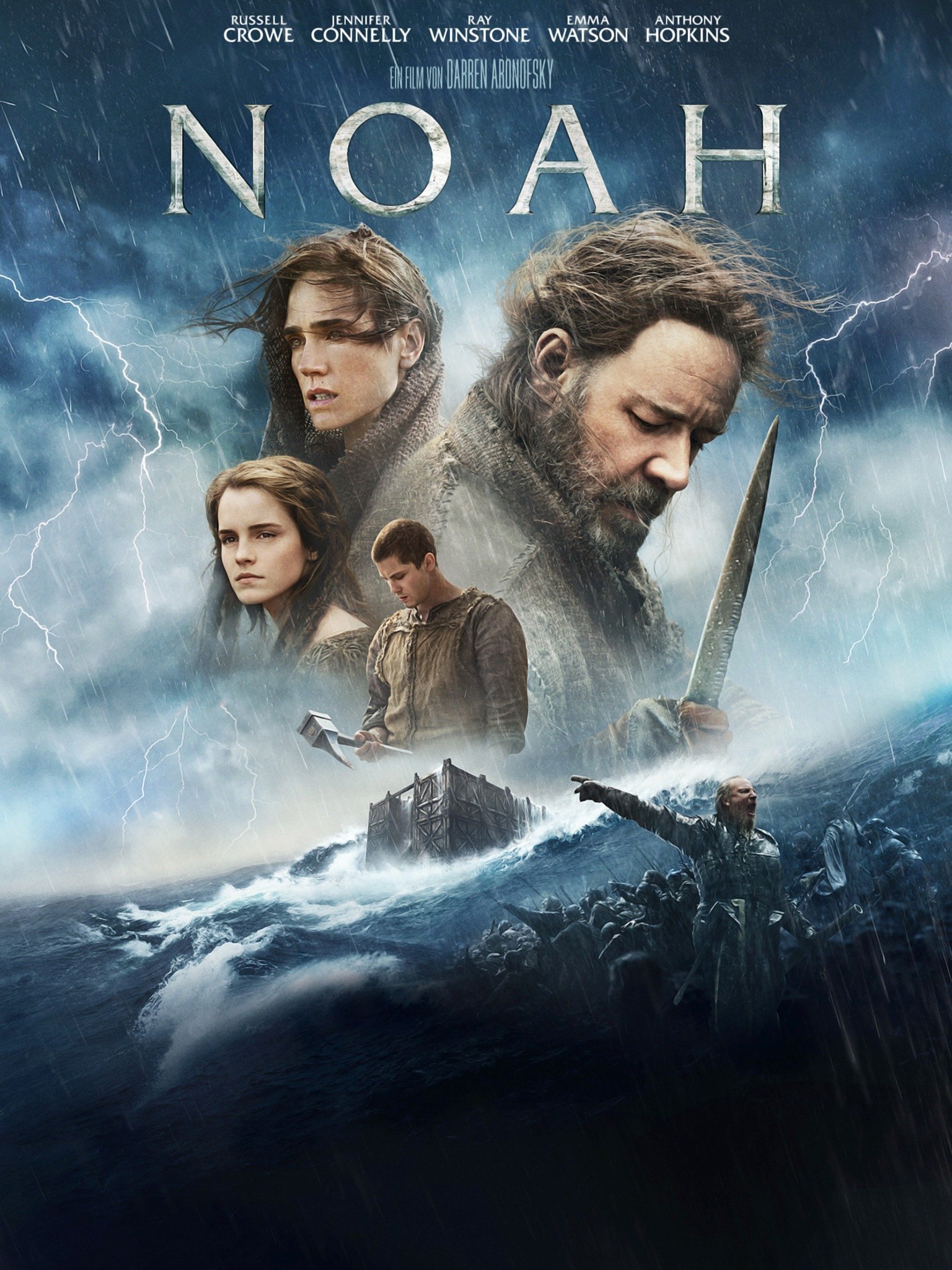

Directed by: Darren Aronofsky

Anyone who goes to see Noah expecting to see the story the way it is usually taught in the Sunday Schools of America will be sorely disappointed. This is not your flannelgraph Noah, and it’s not your flannelgraph God.

What Noah is, however, is a fascinating midrash on the biblical text, using as its framework the flood narrative in roughly the way it appears in Genesis, but with the main pieces of the movie’s story made up almost entirely out of the imaginative musings of the movie’s creator, Darren Aronofsky, and his co-screenwriter, Ari Handel. Beginning with the creation, the film proceeds rapidly to the time of Noah, when mankind has become completely despicable. Crucial to the story Aronofsky weaves are emphases on the Fall in the garden, Cain’s killing of Abel and his banishment to the East, the activities of “The Watchers” (angels based loosely on rabbinic interpretations of the “sons of God/Nephilim” of Gen 6: 2, 4) and the famous judgement on man by God mentioned in Gen 6: 5-8. From the beginning the well-known ecological bent of the movie is obvious. Mankind destroys the creation in favor of building cities and desolating the earth, always acting selfishly in his greed for domination. Noah’s father, Lamech, and his line descended not from Cain but from Seth are apparently the only humans left who care for the earth in a godly way. So the battle lines of the movie are set.

To tell any more of the plot at this point would be to ruin it for those who are reading this but have not yet seen the movie. What can be said, however, is that every Christian should see Noah, if for no other reason than that it raises the huge, overall question of what a filmmaker’s responsibility is to reflect accurately the biblical text.

There are three approaches, it seems to me, those who want to make a movie related to the stories of the Bible can take. First, they could choose to try to reflect the biblical text as accurately as possible. This of course raises many questions immediately. Do you film the movie in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, since these are the original languages of Scripture and the languages in which the inspired text was written down? If not, aren’t you already departing from the biblical texts? If so, who is going to understand the movie in the first place without subtitles, and who is going to go, if it is subtitled? This was of course Mel Gibson’s original intent in filming The Passion of the Christ, and the movie went quite a long way in the production process before they decided not to film it entirely in biblical Aramaic. Even that would not have been to film the biblical texts precisely since, though Jesus and his Hebrew contemporaries almost certainly spoke Aramaic, the text of the Gospels was written down in Greek.

There are variations on the idea of obsessive biblical fidelity that relate not only to getting the look of New Testament sandals correct, but also trying to put in details from the text itself that seem completely irrelevant to us now in order to be complete. Among attempts at this mode of film is the famous “Genesis project”, which attempted in the 1970’s to film the entire biblical text exactly as it is written but only succeeded in filming part of Genesis and the Gospel of Luke. An edited version of the Luke film later became Jesus, the film used in evangelisitic meetings all over the world.

Secondly, one can try to follow the biblical text as closely as possible, strongly trying to relate to the themes as they come out in Scripture, but not worrying so much about the details. This was what many have tried to do in biblical stories from the original silent version of The Ten Commandments all the way through to the recent Son of God. However, this immediately introduces the problem of interpretation in a much stronger way. There is a striking example of this in Son of God in the scene in which Peter comes back to the upper room from having seen the empty tomb. Peter buys bread along the way, sits down before the apostles, tears the bread and says something to the effect of “Jesus is alive. See? This is my body” as he tears the bread in a remarkably Catholic, Eucharistic interpretation of the resurrection. In the same vein, hardly any of the dialogue of Son of God is directly from Scripture but much of it relates strongly to the kind of picture one finds of Jesus in the Gospels, particularly the Gospel of John.

The last, i.e. taking a biblical text as the loose basis for a film and going in an imaginative direction with it, is the direction Aronofsky has gone with Noah. Being quite clear about his own thematic proclivities, he imagines a story of Noah and what it means to be a righteous man in the midst of the evil of humanity. Noah’s psychological wrestlings with his own sin, the evil of mankind, and what that means for the judgment of God and the future of the world are in the end the main focus of this film. It makes for a very lively movie, not only as an action/adventure film, but as a drama bringing to life the complexity of Noah as a character in the story.

I personally found relatively little that was objectionable in Noah, though the mixture of goodness and evil in man is not adequately projected as due to the image of God gone wrong through the fall. In fact the imago Dei is only spoken of as related to the dominion of man over creation, and recognized only by Tubal-Cain, the dominant force for evil in the film. There are other theological problems that I can’t enter into discussion because to do so would be to give away too much of this film.

But that’s why you must go see it, and gather a group of people to talk about it. I suggest your reading Genesis 5-9 before you do, and that you consult the other articles found on the website page of this note for more interesting information on the film.

Drew Trotter