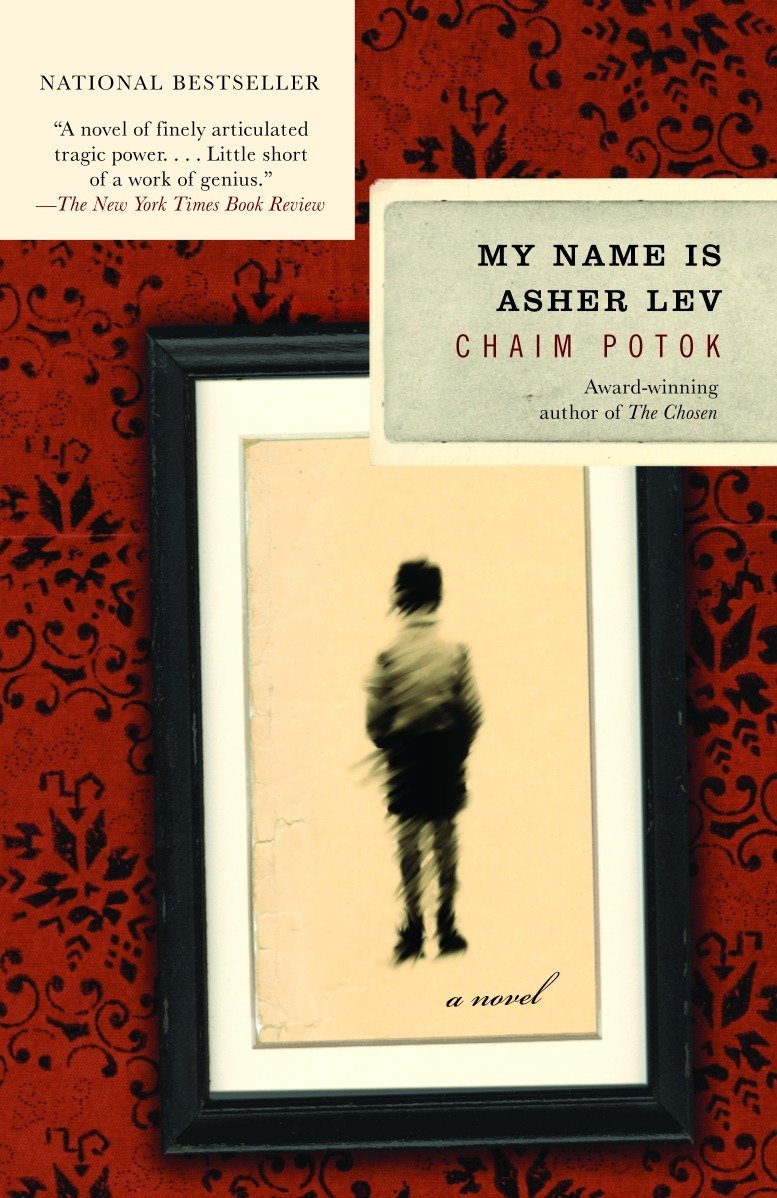

By: Chaim Potok (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972)

Summary:

Asher Lev is a redheaded Hasidic Jew born in 1943 in Brooklyn. He has an almost supernatural ability to draw, yet his faith tradition tries to suppress this. Author Chaim Potok, a rabbi and artist, chronicles Asher’s journey through the years as Asher pleases and displeases, as the boy tries to make a way for his faith and his art to fit together. Written in first person, the novel helps readers learn about the world as Asher does, through his eyes, and at his pace.

Themes, Symbols, & Motifs:

- Duality. Asher thinks, after leaving the Rebbe’s office at the novel’s conclusion, “There was power in that hand. Power to create and destroy. Power to bring pleasure and pain. Power to amuse and horrify. There was in that hand the demonic and the divine at one and the same time.”

- Identity. The story follows Asher’s search for, yes, his identity. Even the title of the book is an ode to this.

- Beauty. As a child, Asher tries to make the world pretty. Eventually, he stops, opting instead to portray the truth. The novel offers that truth is separate from and more important than beauty.

- Windows. Asher’s mother spends considerable time looking through and waiting at windows.

- Journeys. At the end of Books One through Three, a character always says, “Have a safe journey.”

- The mythic ancestor. Asher constantly dreams of his father’s great-great-grandfather.

Discussion Questions:

- Compare the Picasso quote used as the novel’s epigraph—“Art is a lie which makes us realize the truth”—to a quote by Nietzsche in The Goldfinch: “We have art in order not to die from the truth.”

- Jacob Kahn says, “The human body is a glory of structure and form. When an artist draws or paints or sculpts it, he is a battleground between his intelligence and emotion, between his rational side and his sensual side.” The book contains several other discussions on nude art. Are there times when nude art is helpful and appropriate?

- Jacob Kahn says, “Listen to me, Asher Lev. As an artist you are responsible to no one and to nothing, except to yourself and to the truth as you see it.” Do you agree?

- Why does Potok leave so many Jewish terms—yeshiva, Rebbe, Ribbono Shel Olom, Chumash, Hasidim—undefined?

- Asher says, “That’s what art is, Papa. It’s a person’s private vision expressed in aesthetic forms.” Is he right?

- Jacob Kahn tells Asher, “Only one who has mastered a tradition has a right to attempt to add to it or to rebel against it.” Does Asher master painting or Judaism enough to justify his actions at the end of the novel?

- Is the book saying that art and faith can go together? That one helps make sense of the other? Or that participation in the world of art is incompatible with religion?

Drew Trotter