Directed by: Steven Knight

Sometimes a movie’s makers take the chance to do something innovative in the form of their film. They use strange camera angles or they employ a distinctive color palette. The really audacious ones take chances with a different plot structure or with an over–the–hill or relatively unknown cast. Pulp Fiction leaps immediately to mind as a perfect example of this formal daring.

Sometimes a filmmaker or scriptwriter will develop a story or characters or both, which are completely against box–office–success type, pursuing the goal of saying something profound on a social, literary or political topic, but risking the possibility of no one coming and the film losing millions. I think of Robert Altman’s movies Mash and Nashville in this regard. Both did very well, but one could not predict their success. Mash only had an easy time getting made because such powerful people as Ring Lardner, Jr. and Richard Zanuck, loved it from the start and fought for it.

I’m not sure one could name a film in recent memory that is more venturesome in both its formal and thematic elements than Steven Knight’s Locke. Knight is known best for the indie films he has written, and the list is a noteworthy one indeed: Eastern Promises (2007), and Dirty, Pretty Things (2002) are two of the best–respected indie thrillers of the last fifteen years. More interesting perhaps to some readers is his penning of this year’s The Hundred Foot Journey and 2006’s Amazing Grace about the life of William Wilberforce and his battle against the legality of slavery. Each of these movies has a morally virtuous tone without being preachy or other–worldly in its details, and each is well–written and accessible to all types of viewers.

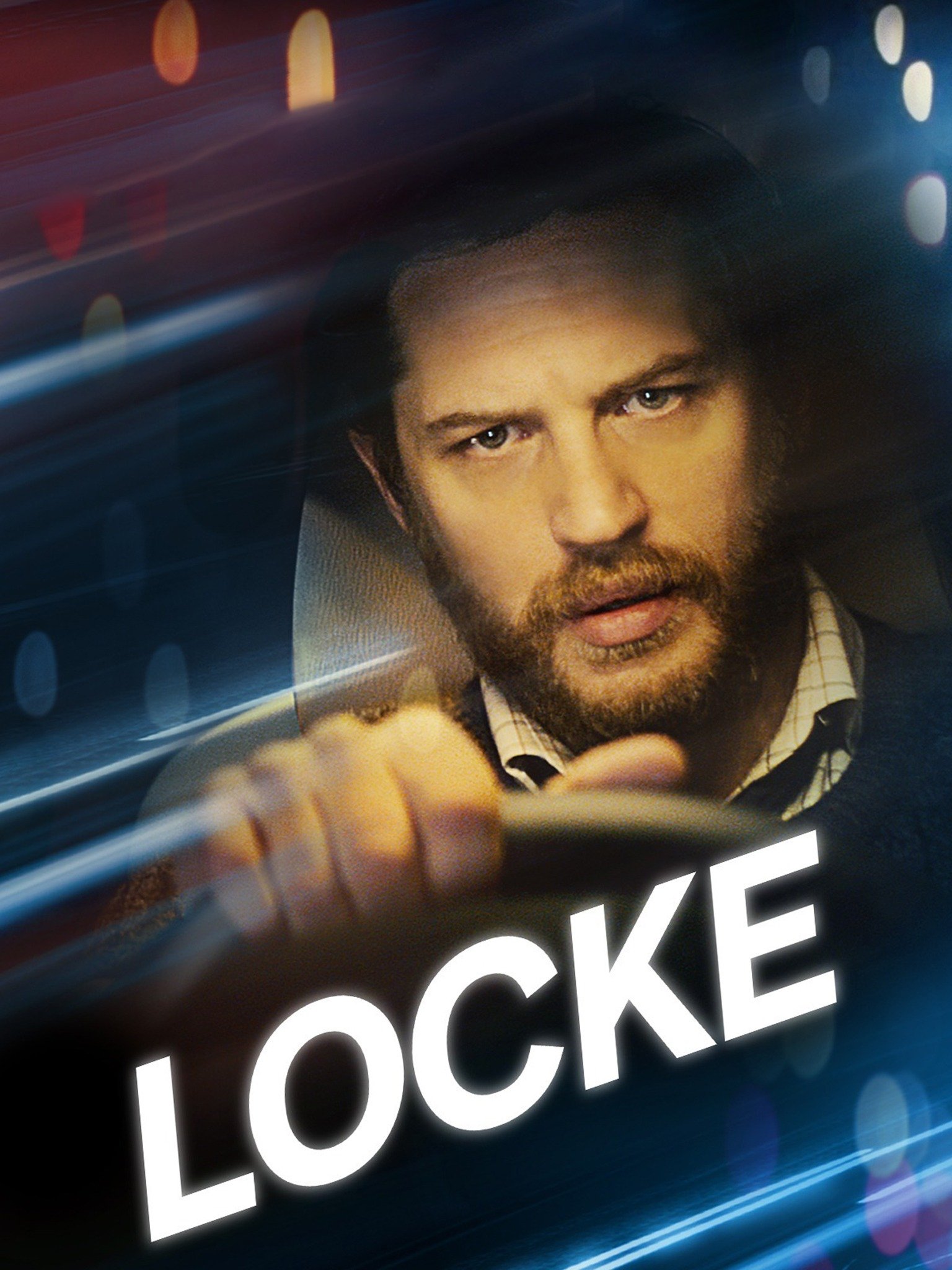

Locke fits well into this oeuvre, but it is radically different from any of Knight’s previous films, especially in its essential formal premise: almost the entire “action” of the movie takes place inside an automobile going from Birmingham, England to London. And further: there is only one person in the car, the rapidly rising star, Tom Hardy, playing the only visible character in the film, Ivan Locke. The film’s story consists almost completely of Locke’s phone conversations with a variety of people over the course of his journey. The viewer hears the voices of the people on the other end of each conversation, but Hardy is the only physical actor in the film. And further still: the film is shot in real time, i.e. the movie runs slightly under one and a half hours and it takes about one and a half hours to travel by motorway (the English for our “freeway”) from Birmingham to London.

All this sounds to most film viewers like a pretty boring evening of film–watching.

But it is riveting. And it is riveting because of the thematic daring Knight has layed over his formal boldness in the movie. Locke is about choice and reason and the ways in which our choices can shape our lives. The title character’s name is a nod to the English philosopher John Locke, known as one of the most influential thinkers of the Enlightenment period. His An Essay Concerning Human Understanding is still a staple of philosophical studies, and his view that human beings develop by experience from the tabula rasa of birth until the grave is the rock upon which much Enlightenment philosophy is built. Reason plays such an important role in Locke’s view of experience, that he could even say it leads us to the knowledge of “a certain and evident truth”: the existence of God.

As Ivan Locke drives, the viewer discovers more and more about what he has done, where he is going, why he is going there and what the implications are for his life of making this trip. In one of the earliest scenes of the movie, Locke sits at a stop light with his blinker indicating he is turning left. When the light turns green, and he remains stationary, reflecting, the truck behind him begins to blow his horn. Locke simply looks at him in the rear view mirror, looks down and thinks, looks up at him again in the mirror, looks down again and then, suddenly, violently changes his turn signal to indicate a right turn and takes off on a trip that will change his life. Not only this choice, but many choices along the way this evening—mostly choices of what to say next—are critical for shaping his future, and each one is worthy of significant discussion.

Locke’s major conversations are with his boss, an underling at work, his wife, his sons, and a woman about to give birth to his child. Each discussion is fraught with significance for him. His marriage is in jeopardy; his job is on the line; and even his psychological state is fragile because of the consequences of his actions.

In spite of all this, Ivan is the calm voice of reason with each of his conversationalists. His boss screams at him because of his leaving on the most critical night of the largest concrete pour in the history of Europe (Locke’s job is overseer of the construction of footings for big buildings). His distraught “mistress” with whom he had a one–night stand, resulting in a pregnancy, tries hysterically to get him to pledge his love to her. His wife, who cannot believe what she is hearing from the always–steady Locke, threatens to lock him out of the house. His sons just want him home as usual, watching the soccer match on television, and are hurt that he has chosen to be somewhere else.

In each of these situations Locke responds with unruffled control. He tells his boss he will take care of the pour through Donal, Locke’s comic associate. He calms Bethan, who is in labor, slowly and carefully telling her to ring the buzzer to get a nurse to close the windows and to give her something for the pain, and that he couldn’t love her, could he, because he hardly knows her. He responds to his wife’s hysterical screams with, “It’s all right, Katrina; it will be all right. We just need to sit down and talk, but it will be all right”. Perhaps most movingly of all, he tries to listen enthusiastically as his sons tell him of the great victory the Birmingham team has won in the match.

As reasonable as he is, Locke is not weirdly unbelievable. When he is off the phone, he screams at the chaos around him out of which he is trying to make order. Ivan talks to his hated, dead father, as if he were sitting in the back seat. He looks around nervously as police cars pass him, or he goes by an accident scene. Then the phone rings again and logic and serenity prevail.

Locke is almost a perfect study of the importance for the human being in a crisis to “keep your head, when all about you are losing theirs”, of the rightness of the fruit of the Spirit of patience and long–suffering. Ivan Locke is everyman, and yet he is a model for every man. He vents when he is alone, as we all must do, but he listens and responds reasonably and calmly, when there is someone on the phone.

I highly recommend Locke for a memorable conversation about choice and reason. By the way, I also recommend you read the blogpost by Consortium member The Comenius Society’s Mark Eckel on Locke. It should stimulate further ideas.

And more about Locke, including portals to reviews, can be found here online.

Drew Trotter