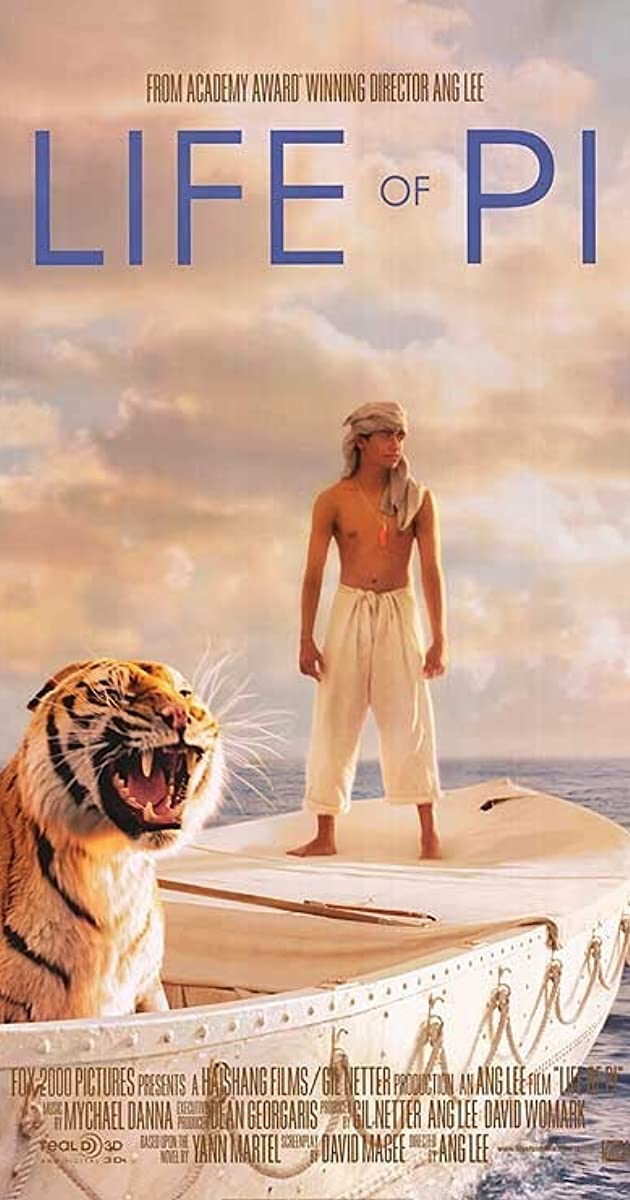

Directed by: Ang Lee

“Is it possible that there are no coincidences?” Mel Gibson’s character, a former priest, asks in the M. Night Shyamalan film Signs. The priest says people break down into two groups: group one sees something unexplainable as more than luck, as a miracle, a sign, and this fills them with hope, for they are not alone; group number two responds to the unexplainable with fear, for they believe they are alone in the universe.

Life of Pi is a film for those in group number one. It is a fable, myth, and allegory, but most of all it’s a parable. This story is and is not real, and we are left with a moral at the end. The moral? Pluralism.

The film, which opened in theaters at the end of 2012, follows Pi Patel, an Indian boy forced to move to Canada. His father brings with them most of the animals from their family zoo. On the way, the ship sinks and Pi spends 227 days adrift at sea in a lifeboat with a 450-pound Bengal tiger.

Pi is our Job and our Noah, for he both suffers and saves. The film teems with more than just Christian references, for Pi is a Roman Catholic-Hindu-Muslim. His choice of literature is ecumenical as well, for we see him reading God-affirming Dostoevsky and God-denying Camus. Even the music is multicultural with hints of traditionally Indian and French sounds.

This cosmic kumbaya is a frame story that is a study in story, but also a study of suffering, God, belief, and fact vs. fantasy. The novel, written by Yann Martel, on which the film is based, has a humorous tone, enabling it to tackle serious subjects—cannibalism, rotting animals, insanity—that the film foregoes. The novel was a huge success, winning the Man Booker Prize, and it even brought about communication with the author from President Obama. The film won four Oscars, including Best Director for Ang Lee.

Names are an avenue where the film’s pluralistic philosophy is revealed. Two characters, a Muslim and an atheist, share the same name, and the tiger, Richard Parker, received his name through a clerical error that gave the tiger’s true name, Thirsty, to the human hunter. The novel intentionally and consistently equates humans and animals and people of other religions, as if their motives and natures are the same.

Pi Patel’s own name is significant and serves as a primer for the essence of the film’s philosophy. He is named after the French swimming pool Piscine Molitor. The film often plays with reflections in water, as if water cleanses and reveals a person’s true nature. Pi studies religion and zoology at the university and concludes that religions are like zoos in that they domesticate, corral, and protect us from the harsh world. Zoo enclosures make life bearable and more pleasant for animals, and so do religions. To live outside the zoo, outside religion, is as hopeless as being adrift at sea for 227 days, or 22/7, which is 3.14—or pi. And supposedly pi, meaning the number, never ends, just as our search for God is supposedly never-ending, for the film implies that God’s manifestations have come from many religions and individuals, from Zoroaster to the Buddha to Socrates to Jesus to Muhammad. As director Christopher Nolan demonstrates in Inception and Memento, what matters most is not what is true but what you choose to believe.

To hear it from the author, Yann Martel says, “The subtext of Life of Pi can be summarized in three lines: 1) Life is a story. 2) You can choose your story. 3) A story with God is the better story.”

A swami I met would agree. I bought cherries from a street vendor in Seattle last summer. He struck up a conversation with me that finished with him suggesting I meet with a friend of his—Swami Bhaskarananda. The next week I had an audience with Swami Bhaskarananda at his monastery. He mentioned unselfishness over and over and finally said, “If a man has a cupcake and he cuts it in half and gives you the other half—this is not unselfishness. The unselfish man would give you his whole cupcake.” Like Life of Pi, Swami Bhaskarananda leveled religions by saying they all teach unselfishness and are therefore ultimately the same.

Life of Pi is religious pluralism disguised as tolerance and ecumenism. Whereas the pluralism-affirming film Book of Eli ends with the Bible being placed beside the Torah, Tanakh, and Qur’an, equating the texts, Life of Pi ends with Pi choosing not what he thinks is objectively or normatively true, but what makes life tolerable. Life of Pi is a silver screen COEXIST bumper sticker, but one of the most stunningly and skillfully presented out there. Let me emphasize that last part. The film is artistically and skillfully rendered. I could just as easily have written a review on the phenomenal special effects, script writing, directing, and cinematography. So, while the message may not match Christianity’s admittedly exclusive claims, or really any monotheistic religion, one should honor the artistic achievement.

Life of Pi takes the binary offered in Signs, that people either have hope in signs or fear in isolation, and presents a way of looking at religions that assures everyone, no matter his or her belief, will be left alone. But if God is everything, then God is also nothing. To affirm every religion is a move so tolerant that it dilutes. Christians bear the name Christian, which means “follower of Christ,” because they have been granted a new identity and a new name. That reformation of the self is exclusive, holy, and enduring; it is maligned when religions are conceived as just man-made stories that enable us to more easily sleep through the night.

Sam Heath