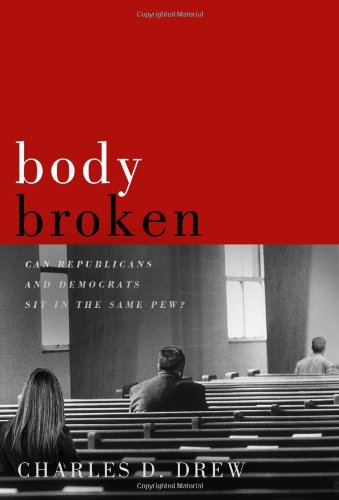

Body Broken: Can Republicans and Democrats Sit in the Same Pew? By: Charles D. Drew (New Growth Press, 2012)

With the political season upon us once again, Christians continue to be in need of guidance as we deliberate upon our vote. This book will not provide the guidance that most probably seek, however. It won’t simply tell you why you should vote one way or another. It does something more useful and more important.

In a thoroughly revised edition of his popular A Public Faith, Charles Drew, pastor of Emmanuel Presbyterian Church in New York City, has given us an answer to the question of his subtitle, “Can Republicans and Democrats Sit in the Same Pew?”. The answer, not surprisingly, is “Yes, but it will take a lot of work.” In simple, straightforward language Drew outlines the problem of why the increasing diversity of political leanings in the evangelical church exists and what we should do about it. The book avoids stridency of any sort, while putting forward five approaches (as he puts it, “some of them attitudes, some of them strategies”) that, if worked out and adopted in the context of our local churches, would change the face of those churches enormously.

Drew centers the reason for the harshness of our divisions over politics as being a fundamental failure to practice in our attitudes and discussions with one another the simple, yet crucial, doctrine of the sovereignty of God over all things. He makes clear that, if we really believed that, we would not tend so often or so deeply to politicize our deepest hopes for our world. Here he agrees with James Hunter in To Change the World (Drew cites Hunter in his introduction as one of his influences) that evangelicals have tended toward politicization and become enamored of power far too much in the latter half of the twentieth century. He centers his discussion of that movement, however, in the more theological language of idol-making, citing particularly the idols of political empowerment and personal privacy as those that prevent us from proper worship of God as God. This reference point tends to make his arguments easily accessible (at least for the Christian) without making them simplistic.

A strength of the book methodologically is that Drew takes common words but then defines them in uncommon ways, forcing readers to re-think what they think they know. For instance, in the last two chapters of the book, he considers the five approaches mentioned above, which he believes we should take to solve the problem of our division: respect, cooperation, diversity, integrity, and simplicity. At first glance, these seem so obvious as to be unworthy of our time. But then, when he explains “respect”, he writes: “We must, in other words, keep public life human.” Jumping off next, as he almost invariably does, from the Bible, he refers to Mary, Nicodemus, Peter, Paul and others and shows how they did exactly that in the “public life” of the first century. The biblical argument is engaging, exegetically precise and entirely winsome. Drew does not, however, stop with the Bible in developing his ideas of “respect”, engaging writings from as diverse a group of people as M.Y. Latsis (the head of Lenin’s secret police) and Edmund Clowney (the well-respected evangelical leader of the latter half of the twentieth century) to illuminate the concept.

Needless to say, this book would serve well any discussion group of students and faculty ready to investigate the question of how we maintain a civil society in the church despite our political differences.

Drew Trotter