Directed by: James Mangold

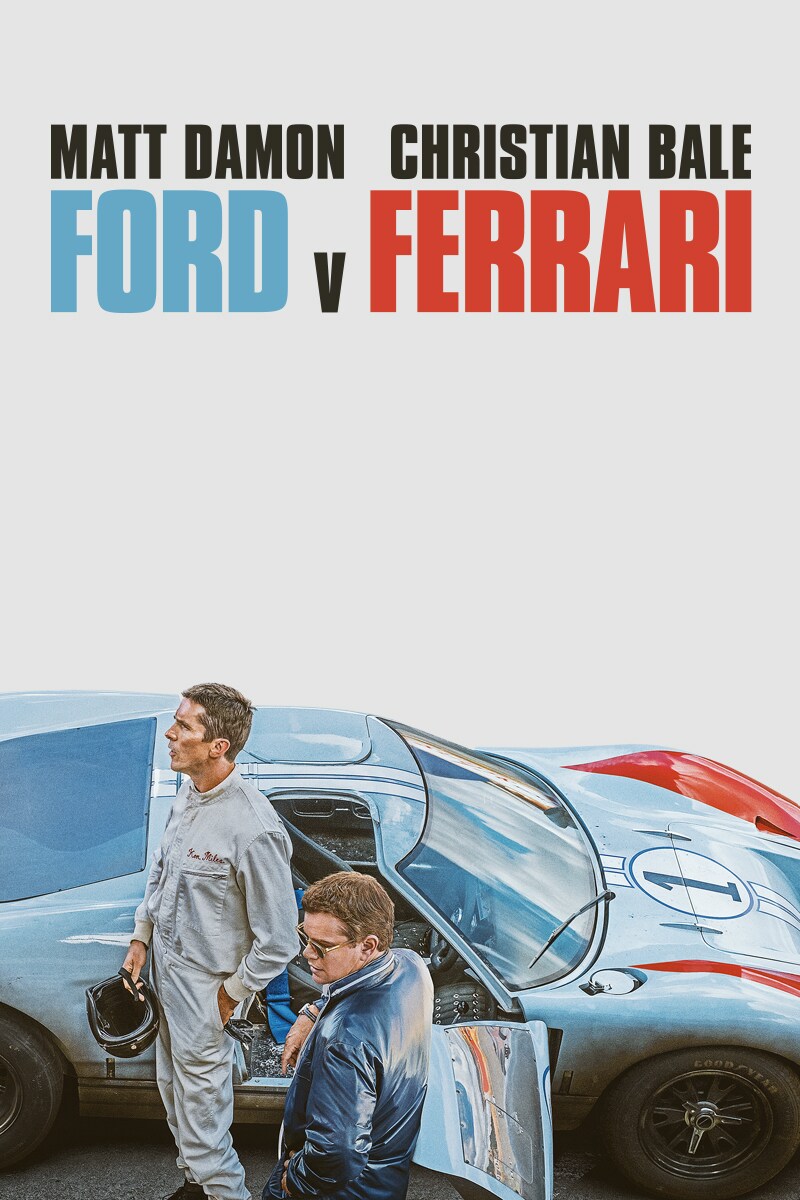

In my last blog post, I announced this series of nine posts, one on each of the films nominated for Best Picture by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. We will look at the nine movies in alphabetical order, starting with the James Mangold helmed Ford v Ferrari.

Ford v Ferrari is not a “racing picture,” though Formula 1 racing, especially the grand-daddy race of them all, Le Mans, is at the heart of the plot. In this context, Mangold has given us a fine buddy picture utilizing two of the best actors on Hollywood’s A list: Matt Damon and Christian Bale. In the hands of these two performers Ferrari has that wonderful blend of being a sports movie with much deeper heart than the plot could ever realize on its own, looking into a variety of themes— perseverance, family vs. work, winning at all costs, corporate greed, the quest for excellence, the nature of friendship, and even the usefulness of words, when the world collapses. Though all these topics are treated in the movie with enough seriousness to make them worth discussing, we will concentrate on a few things the movie teaches us about friendship, perhaps the central theme of the film.

When the historically-based movie begins, the Italian luxury car company Ferrari has won Le Mans five years in a row, and has so outdistanced its competitors that Enzo Ferrari mocks them openly. He particularly picks on Ford, and its owner Henry Ford II. Ford, played by the wonderful Tracy Letts, fed up with his company’s declining sales, decides to follow a strategy pitched to him by Lee Iacocca (John Bernthal) to enter wholeheartedly into racing in order to make Ford a more attractive car to younger buyers. They first try to buy Ferrari, but after appearing to be very interested in selling the company to Ford, while actually using their offer to jack up the price Fiat ultimately pays him, Ferrari says to Ford’s envoy, Iacocca, “Tell him (Ford) he is not Henry Ford. He is Henry Ford… the Second.”

Back in Detroit, Ford decides to get more deeply into racing by building a car that can beat Ferrari. Enter Matt Damon, playing Carroll Shelby, who was the last American to win Le Mans, but has had to retire from racing because of a heart condition. Shelby is asked to design the car and put together a team to beat Ferrari at the next Le Mans, and he immediately hires the high-strung Ken Miles (Christian Bale), the best racer Shelby knows. The movie then proceeds through twists and turns to the finish line at Le Mans, where the inevitable happens: Ford wins but in a way the viewer would never expect.

This is a magnificent film, nominated by many festivals and film awards groups for everything from sound editing to production design to best actor (Christian Bale). It may be the best traditional, linear film of the nine Academy Award nominees for Best Picture, since many of the films this year use a number of different devices to keep the audience’s attention, as we shall see in future posts. There are no tricks, no camera bells and whistles, no editing jumps from here to there—just good, solid filmmaking. Ferrari offers a well-told story, acted superbly by all involved, directed with wisdom and creativity. A story which could have slipped into maudlin melodrama at a number of different places, remains on point the whole 2½ hours plus, holding together several threads without losing any of them or dragging the picture into the deserts of boredom.

The most interesting thematic element is in the friendship between Shelby and Miles, both of whom have gone down in racing history as legends in their fields. The two men were from modest backgrounds, and each was the epitome of the self-made man, so they often sparred. Two of those fights are shown in the film. One is a comic roll around outside in Miles’s neighborhood, his wife Mollie mockingly bringing both men some ice tea when it is over.

The other fight is more serious and more instructive of their friendship. It takes place when Miles’s hot temper loses a sponsorship for them from Porsche. The argument starts slowly, beginning with a disagreement with an official about a small rule they had violated, then escalates into getting Shelby and Miles disqualified from the race. Shelby asks Miles if he likes losing. The short-tempered Miles lashes back, and Shelby, noting that Miles’s son Peter is there, says, “Did you bring your son out here to watch you act like an idiot or to get disqualified? Which?” At this, Miles throws a wrench at Shelby and stalks off. Shelby picks up the wrench and later frames it, giving it to Miles, when Miles actually ends up winning the race. Shelby knows that Miles’s anger was worth tolerating because it was an essential part of his psychological “toolbox”. His relentless quest for perfection, also symbolized by the wrench, was inextricably linked to his anger, playing a large part in making Miles the man he was. Shelby loves him in spite of his faults.

The two men are friends, even though one is the boss (Shelby) and the other the employee. Their friendship is based in a mutual respect for the other’s talent: Shelby the cool, collected manager and designer of the renowned Shelby Cobra, Miles the hot-tempered, reckless, artist who can drive better than anyone in the world. The movie makes clear, as was apparently the case in life, that Shelby’s patience preserved their friendship more than once.

Friendship is a lot of things in the Christian life, but it is always patient and trusting. “…there is a friend who sticks closer than a brother” (Prov 18:24, ESV).

Drew Trotter

March 31, 2020