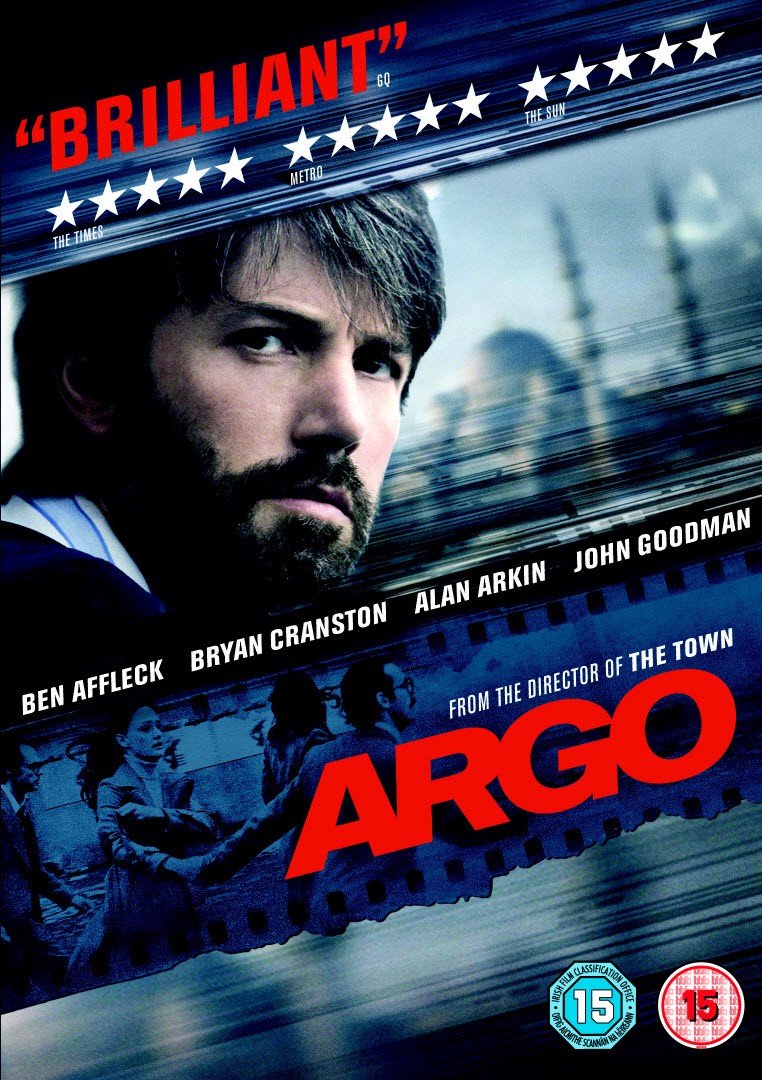

Directed by: Ben Affleck

Argo, the Academy Award winner for Best Picture in a year that may be the best year for nominees since the famous 1939 awards, which featured Gone With the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Stagecoach, et al., describes an historical footnote to the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran and the resulting takeover of the American Embassy in Tehran. On the day of the storming of the embassy, six American diplomats escaped and found their way to asylum in the home of the Canadian ambassador, where they hid for the next ninety days until the CIA could figure out an “exfiltration” for them. The movie largely chronicles the CIA’s process, particularly that of agent Tony Mendez, as they contrived to rescue the six people.

Numerous plans were thought of and discarded by American intelligence. Finally, they agreed upon what is called in the movie “the best bad plan we have, sir”, a scheme to concoct a fake movie for which a CIA agent, Mendez, would act as producer. He would enter Iran, rendezvous with the diplomats, teach them various roles as part of a location scouting team, take them around scouting locations for a few days in Tehran, then shepherd them through security at the airport and take them home to the States. The plan has numerous places it could fail, but the CIA decides to go through with it anyway, and, of course, succeeds magnificently.

Argo is not the most interesting or thoughtful movie the Academy nominated this year, but it is arguably the most entertaining. Shot in the style of the 60’s or 70’s thriller, subplots of Mendez’s love for his son and fear of never seeing him again, the captive diplomats’ worry and distrust of leaving the safety of the ambassador’s house in Iran, the comic development of the background of the movie in Hollywood—all contribute to the tension around the major plot of whether they will succeed or not, or, more precisely, how they will succeed, since everyone watching the picture knows they actually did get the diplomats out. Especially the comedic ventures of Alan Arkin and John Goodman, the only two Hollywood figures who actually know the movie is a fake, play a major part in the movies success. The writing for these two figures is especially good; lines stick in the viewer’s memory for days after seeing the film, and the smart money bets that many of those lines will stick around for some time.

The major entertainment value, though, for most of the audience derives from the tension developed by Affleck and his screenwriter, Chris Terrio, who also won an Academy Award. A certain amount of apprehension resides in whether Mendez will even get the OK to do the job, and later, whether it will be re-approved after a last minute cancellation, but the show stopper is right where it should be, at the end of the film, when the group is trying to get through customs and take off on the SwissAir flight. At the airport, with the added problem of two of the diplomats remaining extremely suspicious of the plan, the group is stopped at check in, removed to a back room, questioned at length, phone calls made to California to the dummy offices of the production company, and a brilliant rescue made by the Farsi speaking husband of the suspicious couple, as he dramatically describes the action in the science fiction adventure film replete with explosive noises of bombs, crashes, machine guns, etc. A great scene, it has the multi-layered result of rescuing the group, elevating the status of the doubting “associate producer”, providing a measure of comic relief, and most of all bonding the group against the enemy by helping them believe they really can pull this off. The tension does not stop there because, after the group is on the plane, the revolutionary guards finally figure out the ruse, chase the group through the various doors of the airport and even chase the plane, trying unsuccessfully to stop its take-off. When the plane crosses into international air space, the huge bubble bursts, the audience sits back in their seats and everyone breathes a deep sigh of satisfied relief.

It is an amazing sequence of scenes. The problem is that none of the events in them ever happened

In Mendez’s book about the incident, he records that the airport sequence was relatively uneventful. While there were minor glitches in that the plane had mechanical difficulties so the flight was delayed for an hour, and one of the diplomats had to explain why his mustache was shorter than in the passport picture, no one really paid much attention to them, and they sailed through. Of course the entire operation was tense, but it—thankfully, of course—lacked the punch and the pizzazz of the film version.

In fact, many elements in the film were made up in order to enhance the story. In the movie, the US administration cancels the operation, but Mendez goes on with it anyway. There is an extremely tense sequence, when the Iranians demand to meet the group in the bazaar to show them some good locations. In the course of the movie, this turns out to be a ploy only to take their pictures to crosscheck them with pictures the revolutionary guards already had of westerners, but it provides a huge amount of tension, as the diplomats and Mendez barely escape discovery time and again. At the airport the next day, the plane tickets are cancelled, then in the nick of time re-instated. At the end of the film, Mendez is reunited with his wife and child. None of these things ever happened (in fact Mendez is portrayed as happily married with two children the whole time). Even the strong theme of distrust of Mendez by some of the group is only mildly hinted at in the book, and not at all in regard to the operation.

Does all this matter? The answer to that question depends on how you view movies about historical events. It has mattered hugely and very publicly to some members of Congress who wrote letters to the filmmakers of both Lincoln and Zero Dark Thirty, complaining that they misled the public on aspects of their films. No one has complained, however, that Quentin Tarantino’s portrayal of slavery in Django Unchained accords better with Caribbean slavery in the 17th century than it does with southern US slavery in the 19th. None of the filmmakers of these movies have made claims other than that their stories are based on the facts of the actual events and that they give the audience an experience of the events that reflects the emotions and experiences of those involved. Whether they do or not, only those who experienced them can say. What we can say is that movies have to be judged on their own merits, and by this criterion, Argo succeeds splendidly.

Drew Trotter