Directed by: Michael Hazanavicius

If someone had told me before last October that a black and white, silent film would be nominated for Best Picture, much less win the award, I would have laughed in their face. I personally don’t even like silent films that much. Because it is my job, I have sat through Birth of a Nation, and King of Kings, but that doesn’t mean I had to like the experience. Even a movie with as racy a title as Flesh and the Devil (1925) with two stars like John Gilbert and Greta Garbo put me right to sleep.

So it was with extreme curiosity that I came to a showing at the Virginia Film Festival last year of The Artist. After the movie, I had trouble figuring out what had just happened to me because I had sat transfixed for two hours, never looking at my watch once, staring at the silver screen like a small boy seeing “the pictures” for the first time. It was an extraordinary experience.

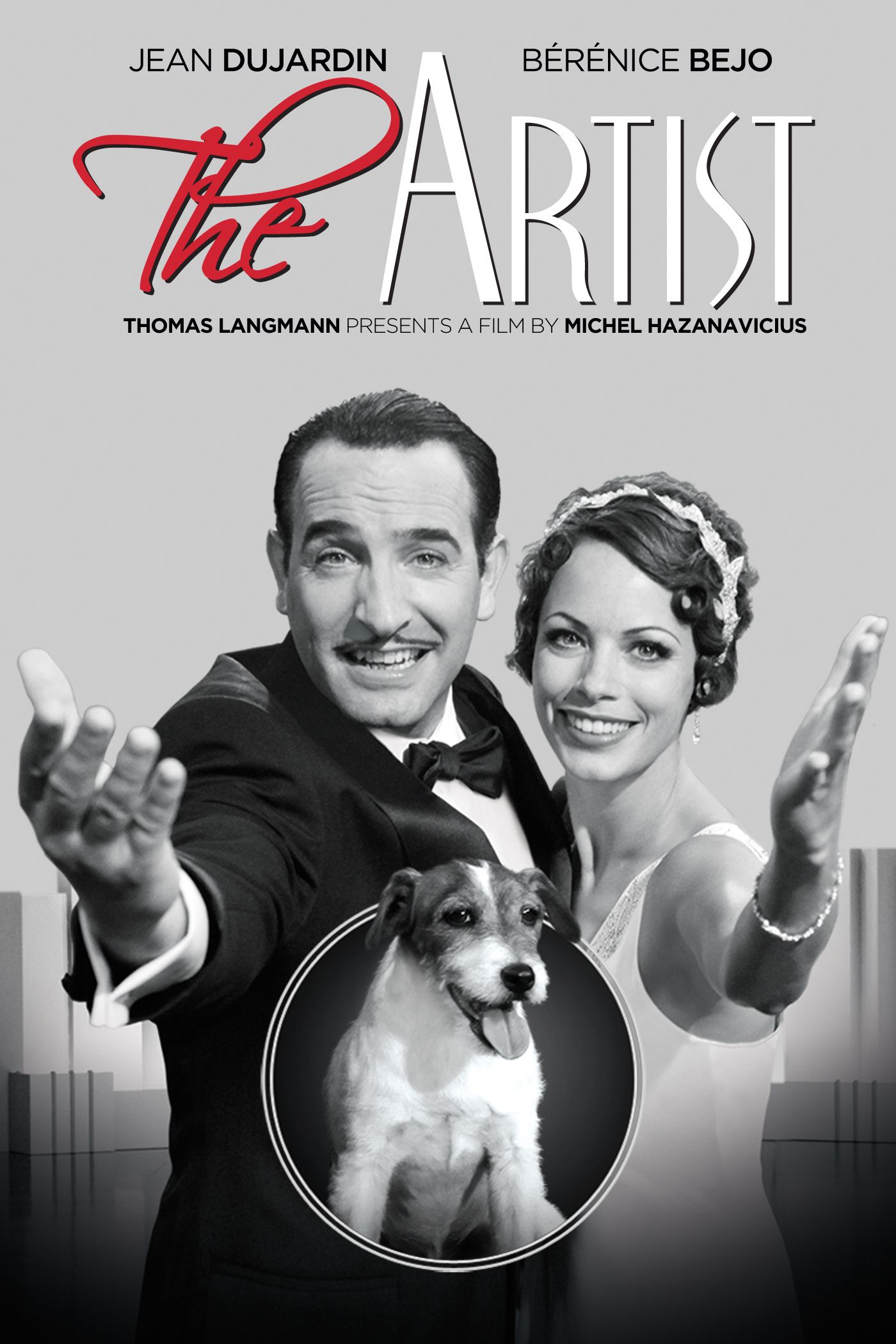

The Artist is that unique combination of great writing, acting, directing, cinematography, and editing that tells a clean (in more ways than one), consistent story well. Basically a riches-to-rags-to-riches story—or, more theologically, a prideful success to deserved fall to repentant redemption story—the movie tells the tale of a successful silent actor named George Valentin, who is a major star as long as the movies are silent. When the talkies come in, his pride, the stock market crash and the rise of a female star, whom he had helped with her first role, cause his demise. The film proceeds through a number of escapades until the two are reunited in a way I won’t tell you because it would spoil the fun, but I will just say that a clever ending of two words, breaking the silence that has reigned throughout the majority of the picture, gives the reason for George’s inability to make it in talking pictures.

The themes of The Artist are standard themes for movie comedies during the whole silent picture era: pride goes before a fall; love conquers all; a good man, down on his luck, comes to his senses, repents, and is rewarded for his humility; a cute dog can make a picture successful. Such themes continue to be the stuff of many great comedic stories wherever they are found; the movies are no exception. So what makes this one stand out? What made it bring audiences to their feet throughout 2012?

To answer that question, it may be useful to say what The Artist is not. It is not a profoundly philosophical movie. This is not Gladiator, consciously exploring the heroic individual who stands for what is right and endures until he is vindicated, or Saving Private Ryan, showing the power of the communal commitment of a squad to a purpose in war that reaches back to home and answers why soldiers are willing to suffer the unspeakable misery of war. The Artist is rather simply a good, old-fashioned movie in the deepest sense of the word, holding up a set of values that are worth believing in, and doing so with a beauty and grace that is hard to deny. Hollywood wants to believe it still stands for that, and so The Artist’s nomination for best picture, and its eventual winning of the prize.

Having said that, I do believe that The Artist has a theme that is discernible, whether conscious or not: the triumph of the individual over his own failings and foibles. Again, this is certainly not uncommon; just look back to last year’s 127 Hours or The King’s Speech for evidence of the prominence of that value in film today. But while in those two movies, the individual would have been lost were it not for family in the first and friendship in the second, in The Artist George Valentin basically pulls himself up by his own bootstraps—or in the words of the Biblical story of the Prodigal Son, “comes to his senses”—, seeks out Peppy Miller, and is saved by her from ruin.

This radical individualism is easily seen in the film. Though Peppy, the chauffer (played by the always good James Cromwell), and certainly the little dog Uggie, all end up playing their parts in helping George come back to full strength, they do not play much of a part in helping him see his pride. His own gazing at his tuxedo in the window of a pawn shop, seeing the near miss he has had in the fire in his apartment, and going along at the end of the movie with Peppy’s idea that can reunite them on screen, all contribute to the notion that, though he could not have come back without the help of others, the final responsibility for his restoration lies with him alone. When he chooses to receive her love for him is when he finally is revitalized.

This theme of the rugged individual making his own choices, pretty much on his own, tells the story of America as much as any theme does, and that is why The Artist would make such a good movie for a discussion of individualism in American life.

Drew Trotter