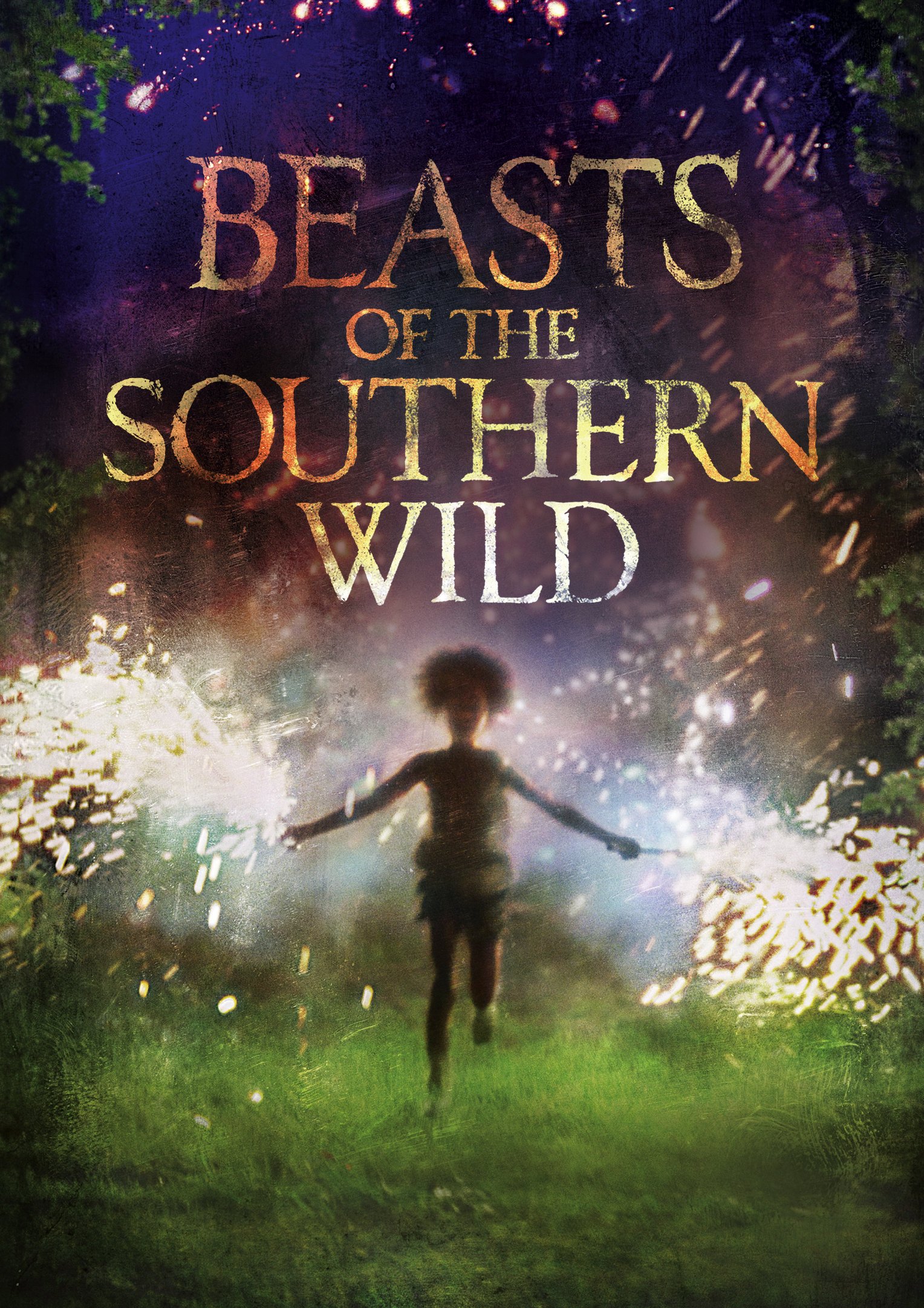

Directed by: Benh Zeitlin

Beasts of the Southern Wild is an example of what is happening in the Academy Awards since the Academy expanded its Best Picture nominations from five to a possible ten: the small independent film that many people really like now often gets a nomination. Like Winter’s Bone (the picture that introduced Jennifer Lawrence to film audiences) from two years ago, Beasts has a intriguing plot, an unknown, well-designed and photographed setting, several stellar performances and enough surprise elements in its story to make it stand out from the pack.

Set in Louisiana in a Delta area called “The Bathtub” because of its position outside the levees, which keep an unpredictable sea out of more genteel areas, Beasts is the story of a young girl, her father and the odd neighbors they have and of their struggle to survive, when a storm arises, threatening their way of life. A strong subtheme of the movie is Hushpuppy’s (played by an extraordinary six-year old named Quevenzhané Wallis) maturation, as she deals with her mother’s disappearance, her love/hate relationship with a volatile father, and her insight into her place in the universe.

Yes, this six year old is no small thinker. From the first shots of the movie in which she is caring for a small bird and listening to various animals’ hearts until her voiceover right at the end (“I see that I’m a little piece of a big, big universe, and that makes things right.”), Hushpuppy relates all she is and does to a larger purpose, or, more precisely, a larger view of the universe and its workings. Wallis was the winner of a vast search—nine months and 4,000 auditions—for the right kind of child, according to Benh Zeitlin, the writer/director of the film. He has said that he was looking for “somebody who had this kind of inner wisdom and had this kind of sense of themselves. Because Hushpuppy is so beyond her years, it was important that we found this kid who was actually wise.” The movie is told from her vantage point with abundant voiceover letting us into her inner thoughts, and they are regularly filled with “big picture” ideas.

But the theme of “child is older than the man” does not dominate the movie, even in its relational elements. Hushpuppy seeks out her absent mother at one point in the film, and the relationship between Hushpuppy and her father, Wink, forms Beasts’ moral center. She often does not listen to him, and often fights him, but almost always with consequences she could not foresee. Wink is the father in a great human struggle against the elements from whom she needs to be able to learn or she dies; in fact, he points to that in another memorable line. As they are getting into the boat to leave the Bathtub, he says, “I’m your Daddy, and you do what I tell you to do, because it’s my job to keep you from dying, ok? So sit back and just listen to me…” The film supports him in this ancient hierarchy of wisdom.

Much more important to understanding this film is a strong, Christian theme of the importance of the connectedness of a people to their land. The residents of the Bathtub refuse to leave when the storm is coming, and this refusal forms the basis for much of the plot of the movie. It also introduces us to the importance of community, of education, and of the sources and cultures of a people—however poor and confused—being the place where meaning is found for them. Unfortunately, the film slips too easily into a shallow pantheism with no nod even to the church or a priest, and certainly no attempt to put its “connectedness to the universe” into a Christian framework, but its strong themes of wisdom, of family, of joy, of perseverance, of opposition to fear and retreat all resonate with the kind of moral stance we should make in confronting the trials and tribulations of a fallen world. When Hushpuppy faces down the mythical Aurochs, the beasts from the southern wild, near the end of the film, she is doing so for all of us, showing us the importance of courage, of understanding what matters most in the world, and of standing for it, even if that means our death. The crucified Christ made just such a stance for us.

Many themes surface in this magical film. Discussions about myth and history, the nature of community, the proper relationship between a father and daughter, a teacher and students, and each of us to the surroundings that shaped us, of the underlying philosophy of the film (Is it Buddhist, humanist, materialist?), of modern medicine and its benefits compared to being ill or dying in one’s home, surrounded by one’s friends—all these themes demonstrate what a treasure of discussion material this film is.

Drew Trotter