Directed by: Alex Garland

The great Sidney Lumet once wrote that he never made a movie unless he could boil down what the script was about into one or two sentences. In his book, Making Movies, he provides the reader with a list of some of his films and their one-sentence themes. Strikingly, no less than three of them, The Anderson Tapes, Fail-Safe and the Academy Award winning Best Picture Network, bore the sentence, “The machines are winning.”

Science fiction is often about the interaction of human and machine, whether it is Transformer style (big, box-office) or Her style (small and personal). One segment of the genre, increasingly prominent in recent years, is made up of films, which explore the battle between machines inhabited by artificial intelligence and the human beings who create them. Perhaps the best of these is the Ridley Scott classic, Blade Runner, but Alex Garland’s Ex Machina is not far behind.

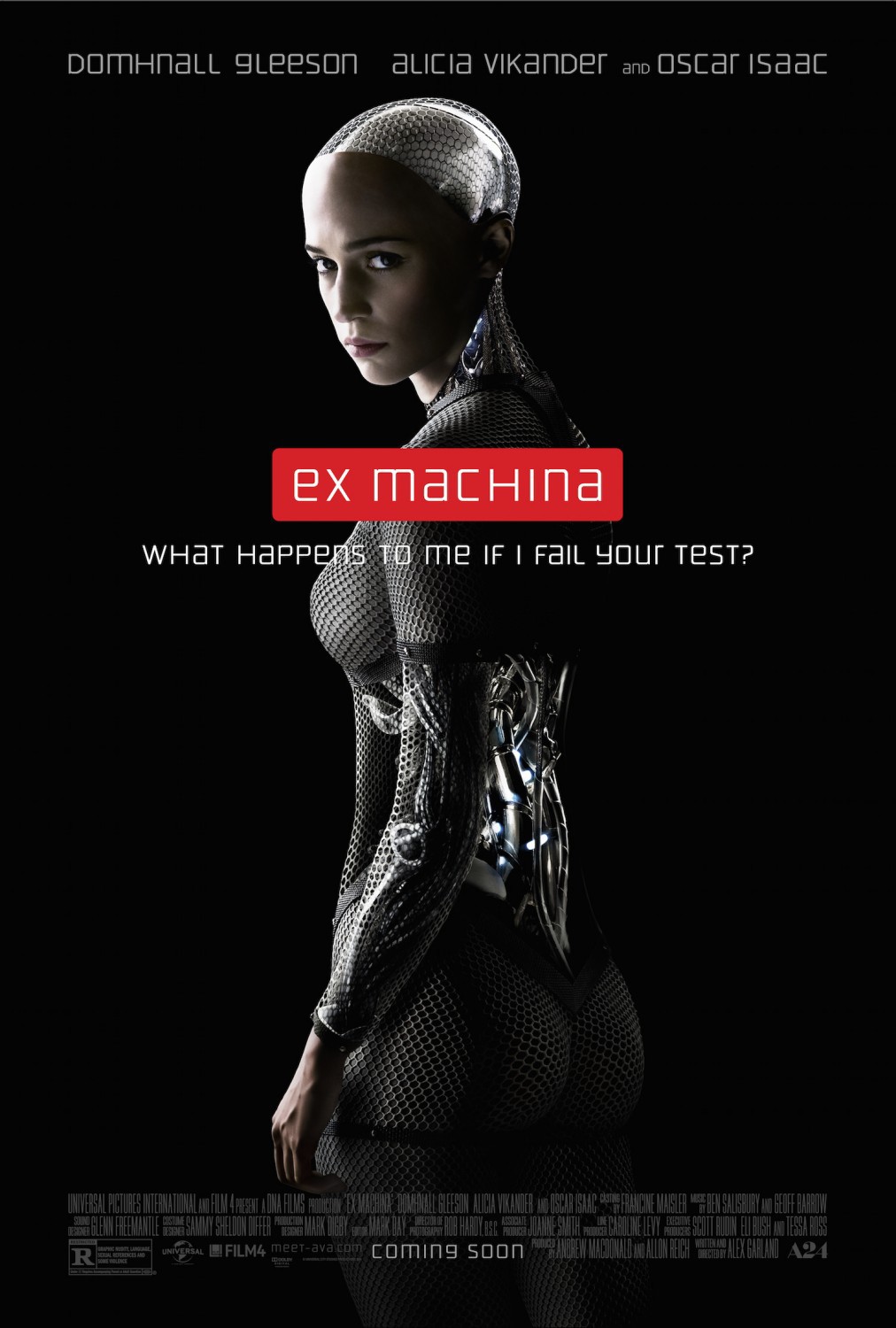

This movie is so smart, so filled with scenes one could spend hours discussing, that it is hard to remember what a great story it tells. A young computer programmer, working at the dominant search engine company in the world, BlueBook, wins a week’s long all-expenses paid, vacation to be flown to the legendary founder of the company’s mountain home and spend time with the recluse, doing whatever he does there. When Caleb, played by Brendan Gleeson’s son Domhnall, arrives, he finds that this isn’t a vacation at all, though he will spend many hours with his boss, a megalomaniac named Nathan, played brilliantly by Oscar Isaac. In fact, Caleb has been selected to be part of a Turing test to determine whether a robot Nathan has created has true artificial intelligence. The robot, Ava, has the face, shape, and voice of a woman, though one can see that the body is mechanical; part of the test is to make Caleb aware constantly that Ava is a machine. The test is to have Caleb meet with and question Ava in order to make his assessment based on her answers.

Though this film rarely leaves the underground bunker that is the home and research center Nathan has created for himself, the viewer is mesmerized by the sessions Caleb has with Ava (in fact the film is divided up into these numbered sessions), and as their relationship develops, one can’t help pulling for Ava and Caleb against the obnoxious, egotistical Nathan. The ending, though it is filled with holes so large one could drive a Mac truck through them, is powerful and receptive of a number of interpretations. The movie is perfect for the proverbial pie and coffee afterward.

Part of the secret of Ex Machina’s attractiveness is the remarkable performances by its four actors, especially Isaac and Alicia Vikander, who plays Ava. As I wrote in a blog post earlier this year, “[Vikander is extraordinary in] the way she is able to control her expressions: just the hint of a smile indicating thorough delight, or the tiny down-turning of the edges of the mouth indicating confusion. And always, always, the mind seeking to understand, or, shall we say, the computer seeking to process. She looks as if she could be Emily Blunt’s younger sister, and, like the older actress, she can be as intelligent a presence on screen as she desires to be.” Oscar Isaac is just as believable, and the role is just as difficult to play. The actor who plays Nathan has to be brilliant, but physically able to be a boxer, sociable enough to be the guy who wants to be your best friend, but irritating enough in the next moment to be the angry boss, who cannot put up with someone who makes mistakes or who is less intelligent than he is. Isaac is able to be all those things and more. Nothing about this film felt false or contrived, and the performances had a lot to do with that.

But there is so much more here than acting and script. All the things that go into a great film are there: a spectacular location and set attract the viewer immediately, but also warn them of danger. The amazing transformation of Vikander’s body into that of a robot, while still making her alluring, and perfect music that moves with the pace and arc of the film in tandem with them contribute deeply to the texture of the film. The dialogue is superb, and leads to the thematic wealth of Ex Machina. One can explore everything from the pedantic psychological themes of the manipulation of people to get them to do things for you they would not do willingly, to pride and its dangers, to the idea of friendship, to what it means to fall in love, to the importance of survival of the fittest for defining the human, to the question of science and its limits. The list goes on.

The R rating of Ex Machina is due to language, some violence and two scenes of female nudity. The rating is appropriate, but nothing about this film is gratuitous.